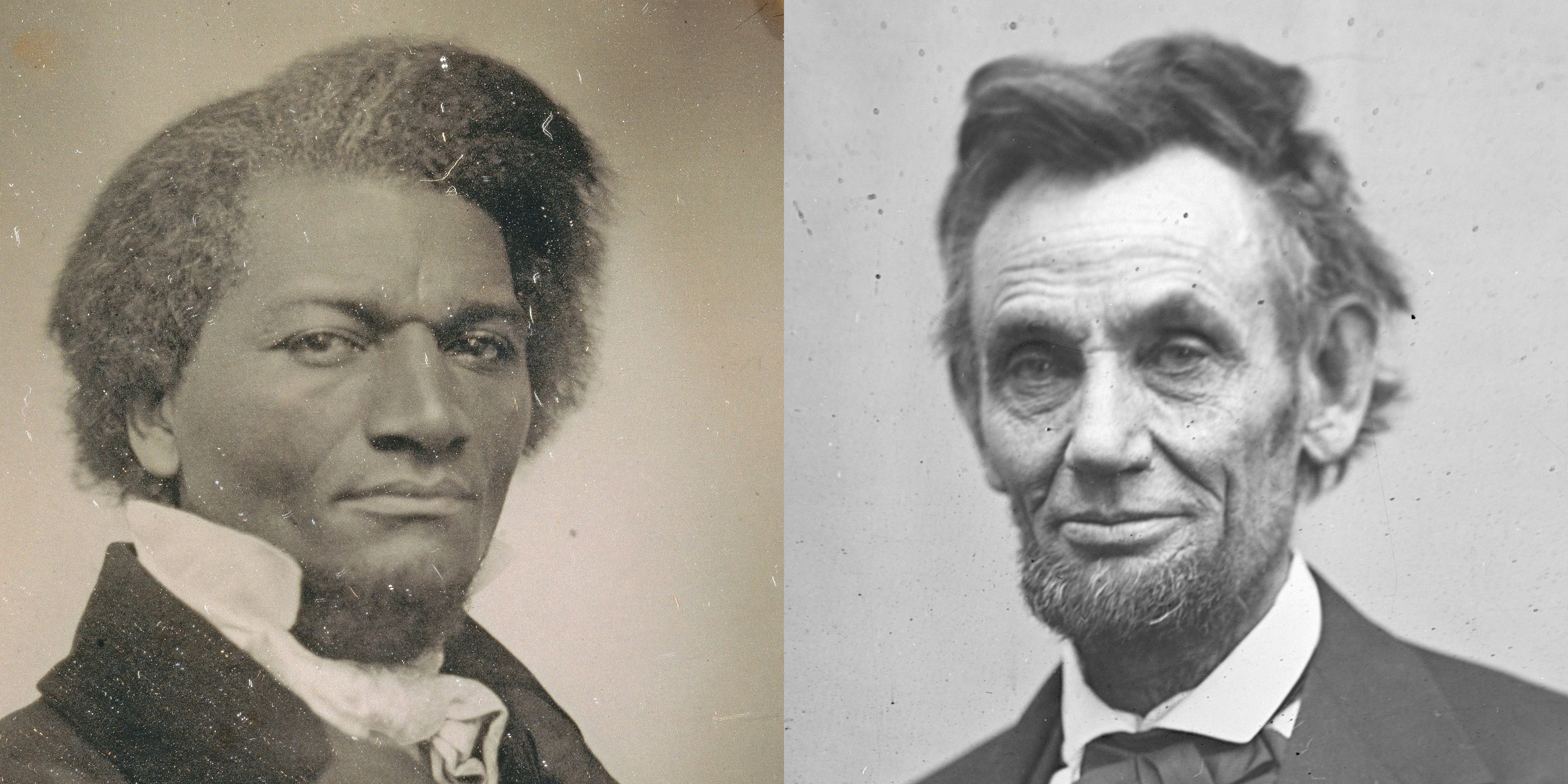

In the middle of the 19th century, as the United States was ensnared in a bloody Civil War, President Abraham Lincoln and abolitionist Frederick Douglass stood as the two most influential figures in the national debate over slavery and the future of African Americans. They met together three times in the White House, and while Douglass was at first harshly critical, he ultimately came to view Lincoln as "emphatically the Black man's president: the first to show any respect for their rights as men."

The first time they met, in August 1863, Douglass was perhaps the most famous Black man in the world. Since escaping from slavery to the North in 1838, he had written two bestselling autobiographies that recounted his journey from a Maryland plantation to lecture halls all over the world as a leading anti-slavery crusader, journal publisher and champion for African American rights. With the Civil War in full stride, Douglass was advocating for the equal treatment of Black Union soldiers. In March, he had issued his famous “MEN OF COLOR to ARMS! broadside calling for Black men to enlist in the Union army. Two of his sons had joined the 54th Massachusetts Black regiment.

Douglass was concerned about the unequal pay of Black soldiers, who received $3 dollars less per month than white privates. He was also incensed by the Union government’s response to the Confederate treatment of Black prisoners of war, who were being tortured, killed and sometimes sold into slavery. He focused his anger at President Abraham Lincoln. “The slaughter of Blacks taken as captives,” wrote Douglass in his Douglass’ Monthly, “seems to affect him [Lincoln] as little as the slaughter of beeves [cows] for the use of his army.”

The First Lincoln-Douglass Meeting

On August 10, Douglass took his concerns directly to the White House—where, uninvited, he later wrote, he “elbowed” his way up the stairs “past all the angry white office seekers” waiting in line. The President, listening intently, explained that the conditions Black soldiers faced were a “necessary concession” for men of color to serve. While that was not the answer he sought, Douglass later told Major George L. Stearns, a leading recruiter of Black troops, that he admired Lincoln’s “decency and forthrightness” and that he left their meeting confident that “slavery would not survive the war and that the country would survive both slavery and the war.”

That first encounter launched a complicated relationship that would last through the end of the war—and Lincoln’s assassination.

“Douglas had been disarmed to an extent by his host’s unpretentiousness and received a political education of a kind,” wrote Yale historian David Blight, of that first meeting in his 2018 biography Frederick Douglass: Prophet of Freedom. “Lincoln too had perhaps learned something of how a Black leader felt about the war for their future and the inhumanities they endured to fight it. The president might also have sensed for future reference how this brilliant radical pragmatist sitting with him that morning might be useful to the nation’s survival.”

Douglass Attacks Lincoln

None of that stopped Douglass from openly criticizing Lincoln. Even with no official job in government, Douglass wielded considerable influence on the national conversation around slavery, Black troop equality and Black emancipation. He did so by traveling the lecture circuit, writing editorials in his Douglass’ Monthly, giving speeches or writing letters to intimates and government officials. In all those outlets, Douglass vented about the president. He had grown impatient with Lincoln’s political foot-dragging on emancipation, since the president felt he first had to overcome widespread prejudice and “prepare the public mind” for its enactment, according to Blight. And Douglass was infuriated over Lincoln’s support for colonizing African Americans outside the United States after emancipation. In Douglass’ Monthly, he castigated the proposal as a reflection of the president’s “inconsistencies, his pride of race and blood, his contempt for Negroes and his canting hypocrisy.”

After siding with the Radical Republican’s dump-Lincoln movement for the 1864 Presidential election and roundly criticizing the president in public for his leniency on the Reconstruction plan and Black suffrage, Douglass was summoned to the White House by Lincoln for a private meeting. No longer a walk-in, he now had a personal invitation from a President facing criticism from every side during a bloody war, and worried about his reelection.

The Second Meeting: A Plan to Rescue Enslaved Black People

At their second meeting on August 19, 1864, Lincoln pleaded for support and guidance from one of his most vocal critics. “Lincoln’s main purpose in initiating this meeting was to seek Douglass’s advice on how to increase the number of Blacks who, in the event that he lost the election, could not be returned to bondage,” wrote Columbia University historian Eric Foner in his 2010 book, The Fiery Trial: Abraham Lincoln and American Slavery.

In his third autobiography, Life and Times of Frederick Douglass, the orator wrote that Lincoln asked him “to undertake the organizing of a band of scouts, composed of colored men, whose business should be…to go into the rebel states, beyond the lines of our armies, and carry the news of emancipation, and urge the slaves to come within our boundaries.”

Despite his best efforts and support from several other Black leaders, Douglass never got a chance to complete the assignment. “It is remarkable that Lincoln suggested such a scheme to Douglass,” wrote Blight in his book, Frederick Douglass’ Civil War. “It would have forged an unprecedented alliance between leadership and federal power for the purpose of emancipation.”

At Lincoln’s Second Inaugural: ‘A Man among Men’

After their second meeting, Douglas became a respected advisor to Lincoln. Invited to Lincoln’s second inaugural address, Douglass was stunned by the president’s eloquence, writing in Life and Times that the 703-word speech “sounded more like a sermon than a state paper.” Reflecting years later on the White House reception that followed, Douglass conceded that while he looked upon himself as a man, “now in this multitude of the elite of the land, I felt myself a man among men.”

When Lincoln spotted Douglass in the throng of supporters at the reception in the East Room, he eagerly sought the Black leader’s response to his address, saying, “There is no man in the country whose opinion I value more than yours.” Douglass replied, “That was a sacred effort.”

Douglass Grieves with the Nation

Five days after General Robert E. Lee surrendered his Confederate army to the Union’s General Ulysses S. Grant in Appomattox, Virginia, Lincoln was shot by John Wilkes Booth on April 14, 1865, while attending a play at the Ford’s Theatre in Washington. Douglass heard the news while giving a speech the next day near his home in Rochester, New York. He told his friends and neighbors that this was a “day for silence and meditation: for grief and tears.”

A few years earlier, Douglass had used the lectern to make sharp criticisms about Lincoln’s handling of the plight of African Americans, but here he was using his platform to celebrate the fallen leader.

That December, in a speech about Lincoln, Douglass lamented how the president’s death had robbed African Americans the opportunity to benefit from his guidance in their new lives as freed people. “Had Abraham Lincoln been spared to see this day, the negro of the South would have more than a hope of enfranchisement and no rebels could hold the reins of Government in any one of the late rebellious States,” Douglass said. “Whosoever else have cause to mourn the loss of Abraham Lincoln, to the Colored people of the Country his death is an unspeakable calamity.”

Lincoln and Douglass: An Uneasy Bond

On the 11th anniversary of Lincoln’s death in 1876, Douglass delivered a speech at the dedication of the Freedmen’s Monument in Washington. His remarks, made during the unveiling of a sculpture depicting Lincoln holding out his right hand over a kneeling former slave, encapsulated the uneasy bond he had with the 16th President.

Pulling no punches, Douglass reminded the diverse audience (including President Ulysses S. Grant) of his disagreements with Lincoln over colonization, the acceptance and treatment of Black troops during the Civil War and the president’s conservative Reconstruction plan. “He was ready and willing at any time during the first years of his administration to deny, postpone and sacrifice the rights of humanity in the colored people to promote the welfare of the white people of this country,” Douglass pronounced. Yet with time, he said, he had come to some appreciation of Lincoln’s pragmatism and political savvy.