The enactment of Prohibition made America’s beer taps run dry, but it caused mobsters’ coffers to overflow from a booming bootleg liquor business. Flush with cash and power, criminal gangs such as the American Mafia transformed into sophisticated enterprises that diversified their illegal activities to include gambling, prostitution and labor racketeering. Mobsters such as Al Capone and New York’s Five Families expanded their underworld empires by infiltrating organized labor. Through intimidation and corruption, the mob used the labor unions for everything from extortion, bribery and embezzlement to price-fixing and kickbacks.

Since the advent of the American labor movement in the late 1800s, gangsters had exploited the division between unions and management by supplying muscle to both sides to break up picket lines or beat up the scabs who crossed those lines. As organized crime syndicates grew during Prohibition, they saw lucrative opportunities in labor racketeering.

“There had always been some unions that operated on the margins of legality by using a measure of force to organize,” says David Witwer, professor of American studies and history at Penn State Harrisburg and author of Corruption and Reform in the Teamsters Union. “In the late 1920s and early 1930s, powerful gangs such as Capone’s outfit in Chicago or the Five Families in New York City move to tax, license or take over…[unions’ business] activities.”

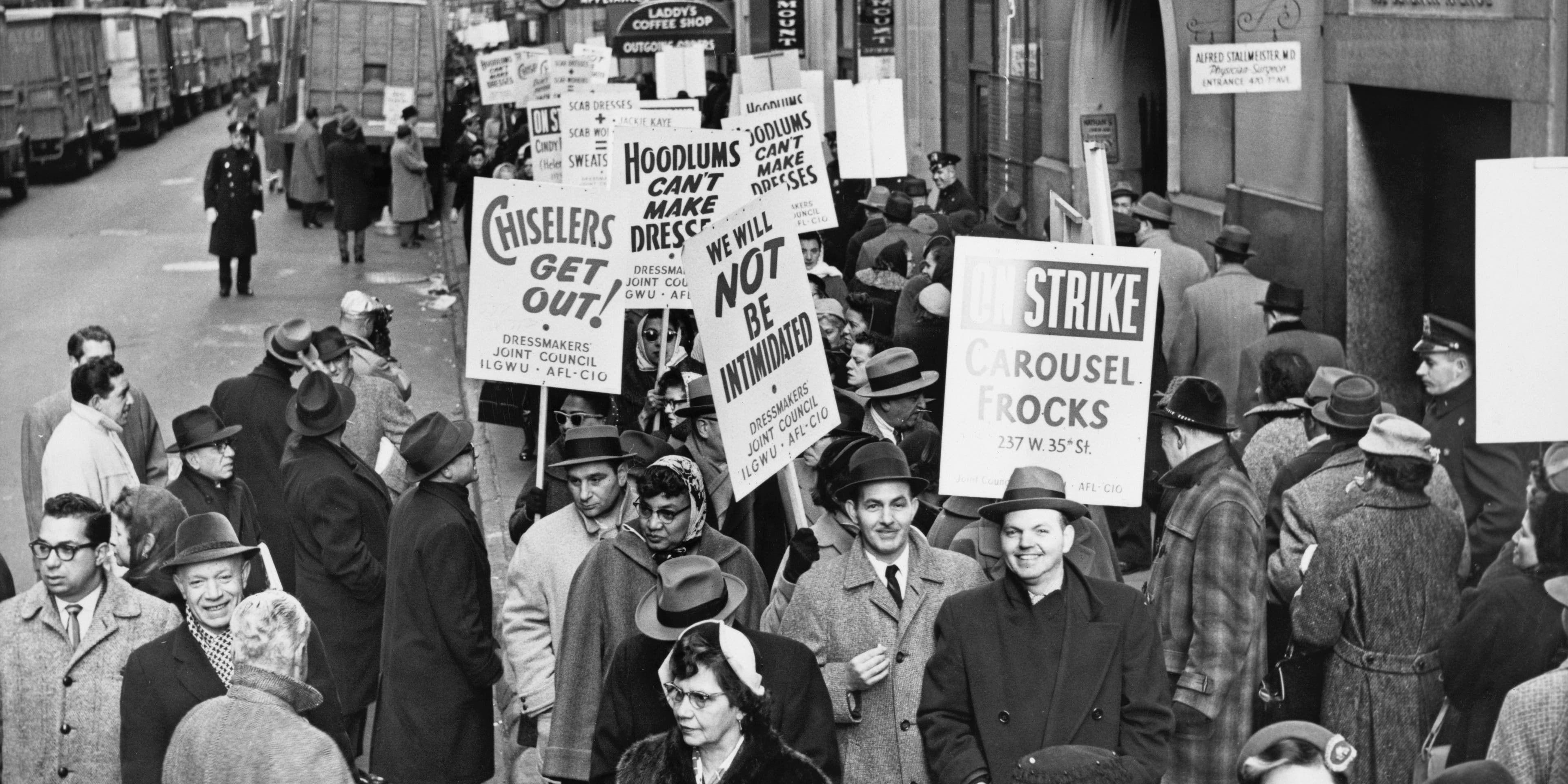

The Mafia targeted unions in low-wage industries known for their semiskilled labor, fierce competition, thin profits and decentralized union structures. In New York City, for example, the Five Families controlled unions in the construction, garment, garbage collection, trucking and restaurant industries. Using bribes and threats of physical violence, mobsters co-opted corrupt union leaders and sometimes installed one of their own in union leadership.

Once in charge of unions, the mob embezzled money from union dues and pension funds and threatened employers with financially crippling strikes to extort payments from them. They paid off corrupt police officers and offered corrupt politicians trade union support in return for immunity from arrest and prosecution.

By 1932, the president of the Chicago Crime Commission asserted that Capone controlled two-thirds of the city’s unions. When organized crime’s monopoly over alcohol evaporated with the end of Prohibition, its grip on labor unions only grew tighter.

American Godfathers: The Five Families

Watch American Godfathers: The Five Families. Available to stream now.

Unions—and Racketeering—Grow During the Depression

Under the New Deal, labor union membership tripled from 3 million in 1933 to 9 million at the end of the decade. With unions gaining power during the Great Depression, the Mafia stepped up its labor racketeering efforts, particularly with local unions in urban centers.

In Chicago, for example, Frank “The Enforcer” Nitti threatened the boss of the Hotel and Restaurant Employers Local 278 if he didn’t install a member of the Capone Gang as president. “If you don’t do what we say, you will get shot in the head. How would your wife look in black?” Nitti asked. With one of Capone’s henchmen in charge, Local 278 instructed its bartenders to push liquors the gang distributed.

In New York, mobsters from the Five Families such as Charles “Lucky” Luciano controlled local unions that operated on the city’s waterfront and shook down all sides. The Mafia took kickbacks from shippers and fishermen to have perishable cargo unloaded. Joseph “Socks” Lanza, head of the local seafood workers union, even took payments from fish processing plants to keep their shops non-union. The costs of all the corruption were passed along to the consumer.

The Five Families and other organized crime outfits also infiltrated local unions of the International Brotherhood of Teamsters and used them to run rackets. With a diverse membership ranging from truck drivers to airline pilots, the Teamsters had become one of the country’s most powerful unions, but notorious for labor racketeering due its decentralized structure with hundreds of local unions.

By the mid-1950s, both labor unions and organized crime had reached a zenith. Taking notice, the federal government launched an investigation into the Mafia’s union ties that captivated the country.

RFK and the Feds Crack Down, Hoffa Vanishes

At the behest of big businesses and anti-union politicians, the U.S. Senate in 1957 established the Select Committee on Improper Activities in Labor and Management—better known as the McClellan Committee—to investigate labor racketeering. The highlight of the three-year investigation was the combative interrogation of Teamsters president Jimmy Hoffa by the committee’s chief counsel, Robert F. Kennedy. The defiant Hoffa denied involvement in illegal activities but admitted to associating with high-ranking mobsters.

The hearings and Hoffa’s testimony tarnished the reputations of American labor. A Gallup poll found support for unions at an all-time high of 75 percent in January 1957, which fell to 65 percent nine months later. Congress responded by passing the Landrum-Griffin Act of 1959, which included anti-corruption measures but also curbed unions’ most successful tactics by banning secondary boycotts and organizational picketing. “Taking away those two really weakens the ability of unions to maintain themselves and organize,” Witwer says, leading to a subsequent decline in union size and power.

Once Kennedy became attorney general in 1961, he significantly expanded the U.S. Department of Justice’s organized crime and racketeering section, making it a priority to investigate Hoffa. Following federal convictions on jury tampering, conspiracy and pension-fund fraud, Hoffa spent four years in prison, still serving as Teamsters president, before President Richard Nixon commuted his sentence in 1971 on the condition that Hoffa not participate in union activities for 10 years.

After breaking that pledge and again seeking the presidency of the Teamsters, Hoffa disappeared from the parking lot of a Detroit restaurant in July 1975 in what the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) believes was a mob hit. Following Hoffa’s disappearance, labor racketeering became a federal law enforcement priority.

RICO Act Bolsters Federal Prosecutions

When the Landrum-Griffin Act proved more effective at weakening the power of organized labor than organized crime, Congress gave federal law enforcement a new tool to combat labor racketeering: the Racketeer Influenced and Corrupt Organizations (RICO) Act in 1970.

The ensuing decades saw high-profile racketeering cases and convictions of labor leaders and mob figures. In the early 1980s, the U.S. Department of Justice brought civil racketeering lawsuits against four international unions, leading to an unprecedented purge of hundreds of criminals from union positions. In 1986, U.S. Attorney Rudolph Giuliani used the RICO Act to obtain convictions of leaders of the Five Families for labor racketeering including fixing bids and demanding kickbacks. While law enforcement agencies continue to monitor Mafia infiltration of labor unions, labor racketeering has become less prevalent than it was decades ago. In part, that’s because union membership plummeted after the McClellan Committee exposed the extent of labor racketeering. At its zenith in the mid-1950s, union membership comprised one-third of the labor force, but now union members only represent approximately 10 percent of American workers.