The ex-president bent over the book, using a razor and scissors to carefully cut out small squares of text. Soon, the book’s words would live in their own book, hand-bound in red leather and ready to be read in private moments of contemplation. Each cut had a purpose, and each word was carefully considered. As he worked, Thomas Jefferson pasted his selections—each in a variety of ancient and modern languages that reflected his vast learning—into the book in neat columns.

Thomas Jefferson was known as an inventor and tinkerer. But this time he was tinkering with something held sacred by hundreds of millions of people: the Bible.

Using his clippings, the aging third president created a New Testament of his own—one that most Christians would hardly recognize. This Bible was focused only on Jesus, but none of his mystical works. It didn’t include major scenes like the resurrection or ascension to heaven or miracles like turning water into wine or walking on water. Instead, Jefferson’s Bible focused on Jesus as a man of morals, a teacher whose truths were expressed without the help of miracles or the supernatural powers of God.

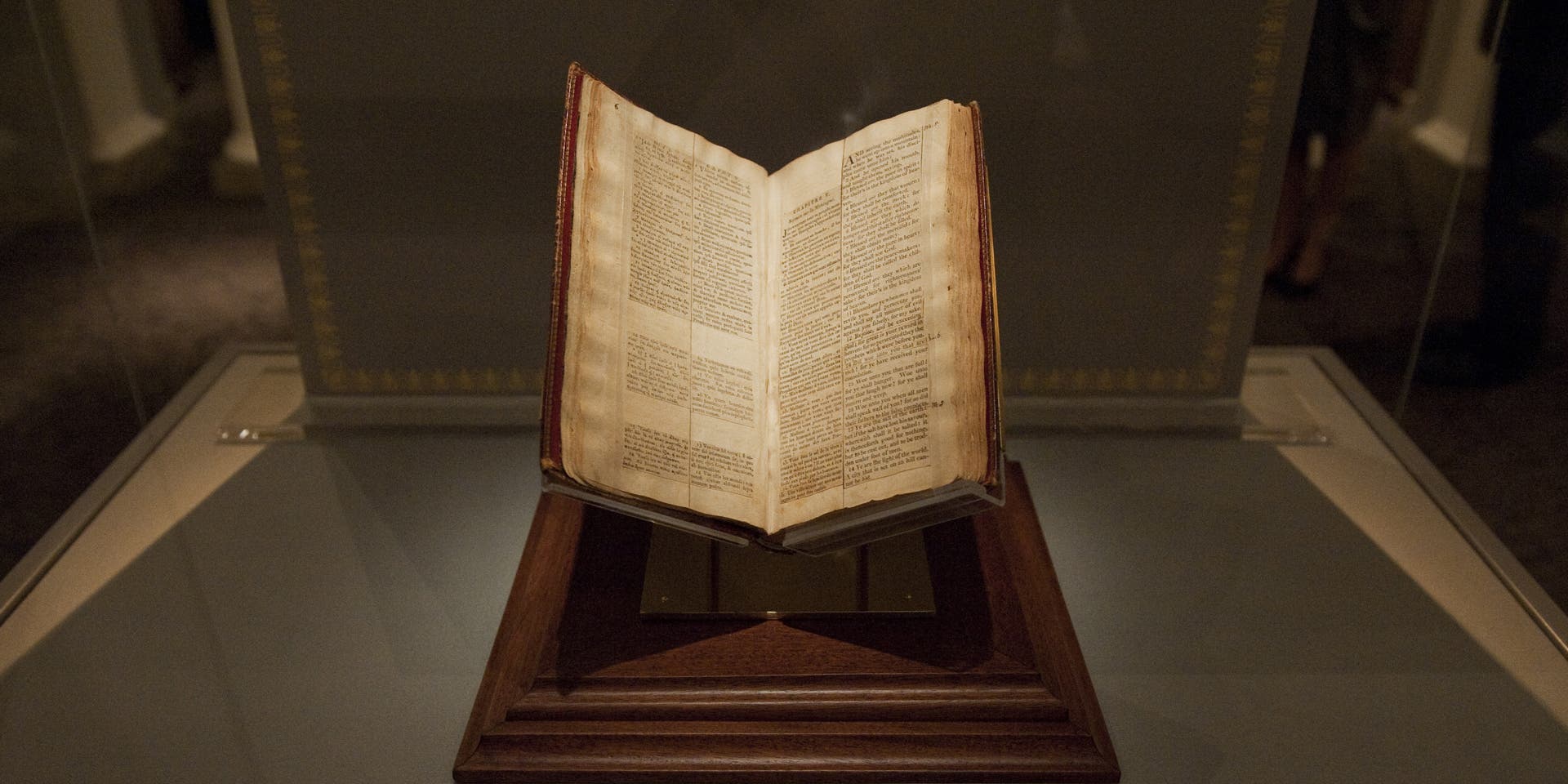

Made for his private use and kept secret for decades, Jefferson’s 84-page Bible was the work of a man who spent much of his life grappling with and doubting religion.

Thomas Jefferson

Watch every episode of Thomas Jefferson. Available to stream now.

Prepared near the end of the ex-president’s life, the Jefferson Bible, as it is now known, included no signs of Jesus’s divinity. In two volumes, The Philosophy of Jesus of Nazareth and The Life and Morals of Jesus of Nazareth, Jefferson edited out biblical passages he considered over the-top or that offended his Enlightenment-era sense of reason. He left behind a carefully condensed vision of the Bible—one that illustrated his own complex relationship with Christianity.

The book was kept private for a few reasons. Jefferson himself believed that a person’s religion was between them and their god. Religion is “a matter between every man and his maker, in which no other, & far less the public, [has] a right to intermeddle,” he wrote in 1813.

But there was another reason for Jefferson to keep his revised Bible private. In the early 19th century, taking a knife to the Bible was nothing less than revolutionary. If the book had been known, argues Mitch Horowitz, who edited a reissue of Jefferson’s book, “it likely would have become one of the most controversial and influential religious works of early American history.”

Jefferson’s editorial work happened in a United States that was deeply rooted in state-sponsored religion. Though many emigrants had come to America to flee religious persecution, laws about religious practice were part of pre-Revolutionary life. Even after the founding of the United States and the ratification of the First Amendment, states used public funds to pay churches and passed laws upholding various tenets of Christianity for over a century after the passage of the Bill of Rights. Massachusetts, for example, didn’t disestablish its official state religion, Congregationalism, until 1833.

Jefferson, a believer in rational thought and self-determination, had long spoken out against such laws while keeping his own views on religion fiercely private. In 1786, he wrote a Virginia law forbidding the state from compelling anyone to attend a certain church or persecuting them for their religious beliefs. The law unseated the Anglican Church as the official church of Virginia. Jefferson was so proud of his accomplishment that he told his heirs he wanted it inscribed on his tombstone, along with his authorship of the Declaration of Independence and his founding of the University of Virginia.

During his political career, Jefferson’s religious views—or lack thereof—drew fire from his fellow colonists and citizens. The Federalists charged him with atheism and rebellion against Christianity during the vicious 1800 election. Among them was Theodore Dwight, a journalist who claimed that Jefferson’s election would shoo in the end of Christianity itself. “Murder, robbery, rape, adultery, and incest will be openly taught and practiced, the air will be rent with the cries of distress, the soil will be soaked with blood, the nation black with crimes,” he prophesied.

Jefferson continued to wrestle with his own views on Christianity after his presidential term ended. His personal correspondence often dealt with religion and religious freedom, and in 1820, when he was 77 years old, he began excising the portions of the New Testament he found unnecessary.

“Even when this took some rather careful cutting with scissors or razor,” writes historian Edwin S. Gaustad, “Jefferson managed to maintain Jesus’ role as a great moral teacher, not as a shaman or faith healer.” Jefferson didn’t intend for the Bible to be read by others, Gaustad notes. “He composed it for himself,” he writes. “He cherished the diamonds.”

During Jefferson’s lifetime, few people knew about the former president’s revised Bible, which he willed to Martha Randolph, his eldest daughter. But in the 1880s, a Johns Hopkins University student, Cyrus Adler, found the cut-up books in a private library. When he learned they were Jefferson’s, he began a search for the book they became.

In 1895, Adler finally got access to Jefferson’s Bible. By that time, the first volume, The Philosophy of Jesus of Nazareth, was lost. But Jefferson’s great-granddaughter agreed to sell the second volume, The Life and Morals of Jesus of Nazareth, to the Smithsonian Institution.

Now the world knew about Jefferson’s private Bible, and from 1904 to the 1950s, incoming Senators received their own copy of the Bible. That practice ended once the government-sponsored printing ran out, but in the 1990s, economist Judd W. Patton revived the tradition and began mailing it to each member of Congress. Today, Jefferson’s secret Bible is held by the Smithsonian Institution, which has digitized the book for anyone to read.